How can teachers and pupil’s use their visual memory

to memorize a story,

internalize it and put their own words to tell it?

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

AN ELEPHANT’S MEMORY!

Storytelling is not learning by heart! It is quite different from memorizing a previously written text down to the last word… it is not theatre. Thus, oral transmission in ancient times allowed speakers to add parts and remove others.

With learning by heart, the slightest omission, even of a sentence leads to a black hole. When you tell a story, you have more flexibility for improvisation, adaptation to the audience, to the context…

In olden times, some illiterate storytellers were able to tell tales for a whole night or even several nights, or to memorize more than 500,000 verses from an epic. Yet these stories were passed on orally. An effort of memorization that hardly seems believable today! How did their prodigious memory work? Above all, they used their auditory memory, with reference points based on rhythm, repetition and melody…

But the storytellers also had storytelling patterns in mind, structures that were often the same and which served as points of reference. Some storytellers said that they followed the character “looking over his shoulder” to better “see” the story unfold, among different “places of memory” located on a map on which they moved throughout their narrative.

💬 This mapped vision, which is not linear, is useful for linking different ideas together and creating thought. This map is like a maze that we draw mentally, and which we have a global vision of, allowing us to test different paths.

In other words, a story map helps tellers ”see” their stories as a series of pictures. It is a representation of the ”skeleton” or the ”bones” of the story, key moments without which the story would lose its meaning. As tellers or children tell the story, they add ”flesh” by telling it in their own words.

The act of creating a map reinforces:

- the visual memory of the story by revising the images in your mind and putting them down on paper.

- the few easy to remember images will help to recollect the whole story in its detail.

This technique proves to be very effective in founding a deep memory that frees a possible improvisation.

HOW TO DO IT?

Before children begin to draw their story maps, you can give the following explanations:

- A story map is not an artistic project: stick figures are fine! It should take 5-10 minutes, not more. A simple pencil should do the trick. Make a series of quick, simple drawings that help you to remember the events in the story in the correct order. Draw the animals as simply as possible. Maybe someone’s drawing won’t make any sense to someone else, but it doesn’t have to. Remember, the map is just for the teller!

TIP: If you have some difficulties drawing animals, just draw a circle and label it with an R if it’s supposed to be a rabbit. - Ask yourself, ”What is the first thing that happened?” Then draw something that helps you remember it. Then think, ”What is the next key moment?” Continue in this way until you’ve drawn scenes to represent all the major events.

Suggestions:

Encourage students to make the story maps without words. However, this does not have to be an absolute rule.

When students have completed their story maps, have them use the maps to tell their stories.

TIP: Those who have not finished within a reasonable time can finish their story maps for homework.

Be sure that less capable students end up with a good story map. If students have trouble doing their own maps, maybe they don’t really understand the story. To help them, suggest that they pick another tale.

💡 Activity 1

The teacher could start building the map with the children to help them identify the key moments of the story. Once the shared element of mapping is complete, you can ask students to create maps of their own.

💡 Activity 2

An alternative idea is to ask the pupils to draw one step on each sheet of paper or card. To help with sequencing, they can then shuffle the cards and put them back in the proper order.

💡 Activity 3

Key moments and moods. Some tellers like to think about the key moments and define their moods, so they are clearer when they tell the story. The moods can be added to the story map. Try figuring the mood of each step on the map.

For example: /beautiful /comic /sad, violent /fury /mysterious /relief /wonder /happy…

💡 Activity 4

A link between school and home. Send the story map home with a note saying something like: “Your child made this map of a story they are learning in class. Ask her/him to tell you the story, and then fill in this form with comments about the experience of listening to it. Thanks!”

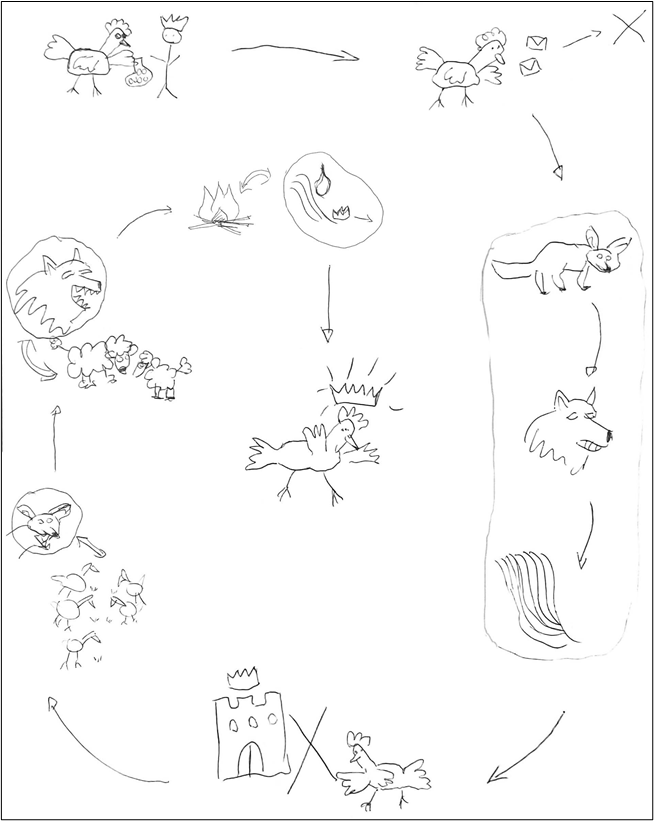

🗺 Example of map 1

Tale “Half a chicken”

Half a chicken leaves his home to claim the hundred crowns the king borrowed from him. On the way there he meets a fox, a wolf and a river and takes them with him. Each of these new friends will help him to convince the king to pay back the hundred crowns.

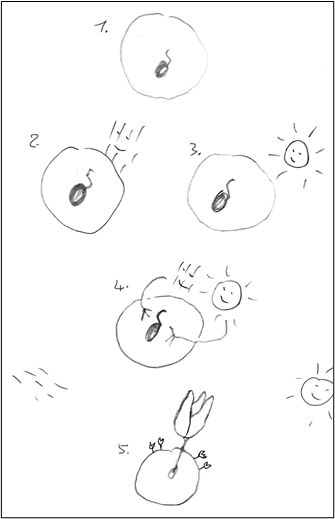

🗺 Example 2

Tale “The Little Pink Rose”

For the youngest

A little pink Rosebud whose determined friends encourage her to leave her home deep under the ground and blossom into the beautiful rose she was always meant to be.