In the beginning were the epics…

The word “hero” alone evokes a sense of adventure, myths, tales and legends that accompany us all. The figure of the hero comes to us from the mists of time with the epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest heroic tale of humanity dating back more than 3500 years.

In our time, when we talk about heroes, we often think of superheroes. But even if they are all-powerful, superheroes always have a weakness. Superman’s weakness, for example, is kryptonite. Overcoming this weakness is the way to merit and glory.

If heroes still fascinate us and have always done so, it is perhaps because, from the outset, they have positioned themselves well, as we would say today: by inviting themselves to the source, in the same texts as the gods.

Gilgamesh, Ulysses, Hercules emerge from epics, stories that explain to an entire community where it comes from and what values it should adopt.

Transcribed on clay tablets in Mesopotamia, the adventure of the famous king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, is also a genesis. We read how the gods shaped men to carry out the most arduous tasks for them. And how the gods, finding these creatures too noisy in the end, tried to drown them… in a story that will be repeated in the Bible.

The same prestigious neighbourhood for Ulysses, Achilles, Hector and the others, who are embodied in The Illiad and The Odyssey. Together with Hesiod’s Theogony (contemporary of Homer, around 800 BC), these texts set the whole of Greek mythology as it can be understood in writing. Almost everything is shown, from the portrait of Gaia to her descendants.

CIVILIZING HEROES

Heroes, whether they are partly of divine descent, or whether they come from the womb of a shepherdess, often have the same defect as the gods: they make little sense. They are, in any case, sufficiently unreasonable to delight the lover of good stories.

Let’s take Hercules, the absolute hero of the Greeks (who, let’s remember, reserve the title either for their most valiant warlords or for demigods). With him, everything starts well. He is of magical birth, the son of Zeus and Amphitryon’s wife, a human (an adulterous, mixed-race pattern, whose recombinations have a bright future). Some sources tell us that his father gave birth to Hercules because he needed a mortal, who alone could rid him of the Giants. Barely born, Hercules already has a mission: to civilise the world.

But Hera, Zeus’ lawful wife, jealous of the birth of this bastard, is going to drive him mad. Hercules grows into a thick brute, his strength multiplying disasters. In a moment of madness, he goes so far as to kill his own children. Ulysses himself doesn’t go along with it, warning: “There are heroes who surpass me and whom I would refuse to challenge.”

From one thing to another, from one blow to another, it is in order to escape the primitive curse of this madness that Hercules will be subjected to the works that have done so much for his posterity. Hercules triumphs over his trials and ends up in apotheosis, on Olympus.

Alongside the gods, the hero, with his difficulties, his moods and his humanity, marks the contrast. He sometimes wears out his entire existence to accept this fragile, transitory humanity and to deploy all its moral and ethical potential. Another witness to the excessiveness of ancient heroes is the cunning Odysseus, who renounces the immortality offered to him by Calypso.

THE HERO’S JOURNEY

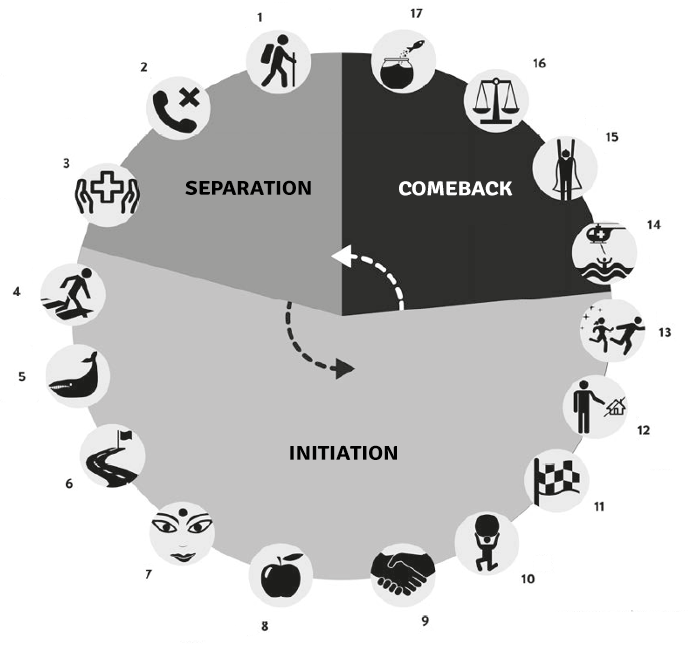

In the immense imaginary territory of heroes, the American anthropologist Joseph Campbell identified, in 1949, a typical pattern that he called “the hero’s journey” in his book, The Hero with a Thousand and One Faces. This pattern is believed to be embedded in the unconscious of humanity and is one that we all share.

Legend has it that the creator of Star Wars, George Lucas, wandered from rejection to rejection with Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader on his hands until he discovered this pattern, passed on by Scorsese or Coppola (depending on the source). Then, all that remained was to rewrite the whole saga, following this magic potion step by step, and here are the main steps. This roadmap has become a classic in writing courses and in the manuals of the apprentice screenwriter.

Separation

- The adventure’s call

- Refusal of the appeal

- Supernatural help

Initiation

- Crossing the first threshold

- The belly of the whale

- The path of trials

- Meeting with the goddess

- Temptation

- Reunion with the father

- Apotheosis

- The supreme gift

- Refusal of return

- The magical escape

Comeback

- Deliverance from the outside

- Crossing the threshold on the way back

- Master of both worlds

- Free in front of life

ACTIVITY

For older students: invent a story together based on the main stages of the hero’s journey.